King Edward / Lambert Simnel

Ten months after the Battle of Bosworth, on Sunday 27 May 1487,1 a young boy was crowned King Edward of England in Christ Church Cathedral, Dublin. Present at his coronation was King Richard’s friend and former Chamberlain, Francis, Lord Lovell, and the Yorkist heir to the throne, Richard III’s nephew, John de la Pole, Earl of Lincoln. Lincoln, the eldest son of Richard’s sister Elizabeth, Duchess of Suffolk, had seemingly been heir presumptive during King Richard’s reign and, if Richard had fathered no legitimate heir would have ascended the throne as John II of England. Also present at the coronation in Dublin were the leaders of the Irish church and the Irish nobility. The Irish had been long-term supporters of the House of York.

At the battle of Stoke Field, on 10 June 1487, the Yorkist army, fighting on behalf of King Edward, was defeated. Lincoln was killed and Lovell seems to have escaped, although it is not known what became of him. It is also unclear what happened to ‘King Edward’. Some reports state that he died on the field, others that he was sent to safety by his cousin, Edmund de la Pole. However, following the battle a boy who had been taken prisoner, was said to be the king who had been crowned in Dublin’s cathedral. The boy, although seemingly called ‘John’, was given the name of ‘Lambert Simnel’ and forced to work in Henry VII’s kitchens. He later became a falconer. Henry VII ordered the immediate destruction of all records in Ireland pertaining to the boy-king's coronation and Parliament. Two years after the Battle of Stoke Field when the Irish lords attended a banquet in London given by King Henry, they were served by this same kitchen boy. None of the Irish lords present recognised him as the boy crowned in Dublin. However, when they were informed of the servant’s ‘identity’ one of the lords said he recognised him as the boy-king. It is not known whether Elizabeth of York ever met Lambert, or asked to see him. Whether Lambert Simnel was indeed the boy-king crowned in Dublin has been hotly debated ever since.

For information about Simnel as Edward V, the missing Prince and eldest son and heir of Edward IV, see author and historian, Matthew Lewis here. You can also view it on Matthew’s website here.

For information about Simnel as the son and heir of King Richard’s elder brother, George, Duke of Clarence, see author and historian, John Ashdown-Hill, The Dublin King (2015).

1. From a number of sources including the Red Book of Ireland. See: Randolph Jones, Ricardian Bulletin (June 2009), pp.42-4, and Ricardian Bulletin (September 2014, pp.43-5. Also Academia, Medieval Dublin XIV (2015), pp.185-209, specifically Appendix 1: ‘The Revised Coronation Date of Lambert Simnel’, pp.207-209. In the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries a Sunday was the appropriate day for a coronation. It is not known why Henry VII’s Parliament recorded the date of the Dublin coronation as 24 May (a Thursday). This may have been a deliberate attempt to undermine the credibility, and legitimacy, of the ceremony, and thereby its anointed king.

For the most recent research and archival discoveries concerning the continued life of Edward V into the reign of Henry VII, please see here.

Richard of England / Perkin Warbeck

In 1491, a young man recently arrived in Ireland declared himself to be Richard, Duke of York, the youngest son of Edward IV of England and one of the missing Princes. The boy claimed that from 1483 to 1490, when he was assumed to be ‘missing’, he had lived in various places in Europe under the protection of two loyal Yorkists. However, when one of them died and the other returned to his country, the boy was left alone. It was around this time that he declared his true identity as Richard duke of York, or Richard of England, as he chose to call himself.

By 1493, Richard of England had garnered a significant following and, most importantly, the backing of Margaret, Dowager Duchess of Burgundy, sister of Edward IV and Richard III. The young man bore a striking resemblance to his alleged father, Edward IV, and had the same three body marks said to have been apparent on the king’s youngest son. He also recounted details and conversations from the English court that only King Edward’s youngest son would have known, and revealed an intimate knowledge of the English court and its workings. He also spoke courtly English. As a result the crowned heads of Europe believed him to be Richard IV of England.

In 1495, a plot in support of Richard of England was uncovered with Sir William Stanley (victor at Bosworth and Henry VII’s Chamberlain) its titular head. Following a summery trial, Sir William was executed at the Tower of London. A significant number of King Henry’s leading courtiers were also found to be involved in the plot and many of them were subsequently executed. Sir George Buck, an early biographer of Richard III, questioned many of those whose relatives were alive at the time, and estimated the number of rebels to be in the hundreds.

Following two failed attempts to claim the English throne 'Richard of England' was eventually captured in 1497. Allowed to live at King Henry’s court, he was separated from his wife (Katherine Gordon), and young son (Richard). It is not known what became of his son. Elizabeth of York, the young man’s purported sister, was not allowed to see him. Following an escape attempt, 'Richard' was re-captured and imprisoned in the Tower of London where he was badly beaten so that his face was unrecognisable. Paraded through the streets of London and mocked, he had signed a paper confessing that his name was Piers Osbeck, a boatman’s son from Tournai in France. It is not known why the young man didn’t sign his confession as Warbeck, the name given to him by King Henry. ‘Warbeck’ was hanged as a traitor at Tyburn in London on 23 November 1499. It was never explained how a French citizen could be convicted and hanged as an English traitor.

Five days later on 28 November 1499, a young man said to be the son and heir of George, Duke of Clarence, was beheaded at the Tower of London. The boy had been held as a prisoner in the Tower for some 14 years, following Henry’s victory at Bosworth. In the months following the executions of these two young men, it was commented that King Henry VII aged twenty years in two weeks.

For the most recent research and archival discoveries concerning the continued life of Richard of England into the reign of Henry VII, please see here.

Research in the Low Countries

As a result, a significant line of investigation for the project is the on-going research in the Low Countries (Netherlands, Belgium, Northern France and former Burgundian Netherlands) in the location where York/Warbeck spent much of his short life and Edward/Simnel prepared his invasion of England with the Lords Lincoln and Lovell. With much of the archival material in England destroyed during the reign of Henry VII (see above and Archival Destruction here), records in the Low Countries, by contrast, seem to have survived relatively intact.

One of the leading teams for the project is the Dutch Research Group, led by Nathalie Nijman-Bliekendaal, and based in the Netherlands. From time to time, some of their research will be published.

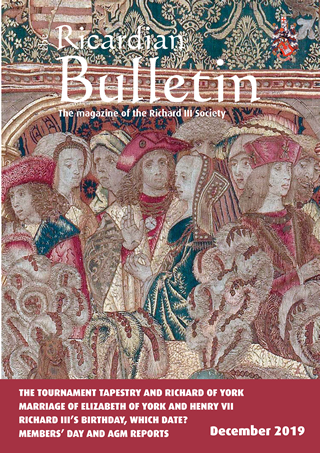

We begin with a remarkable discovery by Nathalie in the Tournament Tapestry of Valenciennes and its apparent depiction of Richard of England at the Burgundian court in 1494.

Does the TOURNAMENT TAPESTRY IN THE MUSEUM OF VALENCIENNES represent ‘The New Young King of England’ among the royal spectators?

In ‘The Tournament Tapestry of Valenciennes’ Nathalie Nijman-Bliekendaal © 2019 considers the contemporary material surrounding this remarkable tapestry and whether the artwork depicts the young man claiming to be Richard IV of England, the youngest son of Edward IV. First published in the Ricardian Bulletin magazine of December 2019, pp.45-53, you can now view this article here.

Our very grateful thanks go to John Saunders, editor of the Ricardian Bulletin magazine, for his kind permission to publish this new research here for you.

Following the publication of Nathalie Nijman-Bliekendaal’s article on the Tournament Tapestry at Valenciennes, two interesting letters were received by the Ricardian Bulletin magazine. We are delighted to be able to publish these here for you. The first letter comes from Marilyn Garabet, a researcher of many years standing into the life and times of King Richard III, and concerns the eyes of the young man depicted on the tapestry. The second letter comes from Keith Dowen, Assistant Curator of Arms at the Royal Armouries, and concerns the possibility that the tapestry may date from a much earlier period than 1494. Our thanks to Marilyn and Keith for raising these important questions. Please see below for the questions, and Nathalie’s response.

The Tournament Tapestry: From Marilyn Garabet, Ricardian Bulletin (March 2020), pp.3-4.

I read my Bulletin with great interest, as usual, and was fascinated by the article about the Tournament Tapestry. Another factor in favour of the unidentified man being Perkin Warbeck is the depiction of his eyes. Henry VII’s envoy, Richmond Herald, remarked to the Milanese ambassador in 1497 that the young man’s left eye was defective and lacked a little brightness, ‘que manca un poco da strambre’, and that, for this reason, he was ‘not handsome’. Ann Wroe believes this disfiguring blemish can clearly be seen in the Arras sketch (see Ann Wroe: Perkin; a story of deception, Vintage 2004, pp.9-11). Francis Bacon unkindly refers to Perkin’s defective eyesight when he tells how the young man began ‘to squint one eye upon the crown and another upon the sanctuary’ (Francis Bacon: The History of the Reign of King Henry VII, Hesperus Press Ltd, 2007, p.126).

Certainly, the young man depicted on the Tournament Tapestry has eyes of different shapes and sizes, one possibly having a squint and the other noticeably smaller and paler with distinctive lines at the corner which could indicate scars from an injury. It would be interesting to see an enlargement of this part of the tapestry, which could, indeed, show a true, rare likeness of the man known as ‘Perkin Warbeck’.

The Tournament Tapestry: From Keith Dowen, Ricardian Bulletin (June 2020), pp.3-4, with Nathalie Nijman-Bliekendaal’s response to both Marilyn and Keith’s letters, Ricardian Bulletin (June 2020), pp. 21-24. You can now read these here.

The King’s Speech: Richard of England in his own words

In the autumn of 2020, The Missing Princes Project began an investigation into a quite remarkable document - Richard of England’s Proclamation from Scotland in September 1496. In presenting himself as the youngest son of King Edward IV and rightful King of England, King Richard IV, he became known as Perkin Warbeck. As a result the identity of this individual is a key line of investigation for the project. Our investigation began with the copy of the Proclamation from Diana M. Kleyn’s, Richard of England. Interestingly a different copy was located in Jean-Didier Chastelain’s, ‘L’imposture de Perkin Warbeck’. As a result, project member, Dr Judith Ford, agreed to investigate this important contemporary source in order to throw what light she could onto it. Judith’s investigation reveals a number of potential new discoveries - in the documents provenance and connection to the Howard family, but also in Richard of England’s message within the Proclamation that may relate to Richard III, and which Sir Francis Bacon would later recognise as such.

First published as the cover story in the Ricardian Bulletin magazine of March 2022, pp.48-53, you can now read Judith’s important new research article here.

You can also now read Judith's transcription of Richard of England's Proclamation of September 1496 from the original manuscript here. Together with the modern transcription here. This is the first time Richard IV's Proclamation has been made available. With especial thanks to Dr Judith Ford.

Our very grateful thanks to Alec Marsh, editor of the Ricardian Bulletin magazine, for his kind permission to also publish this new research article here for you.