Who were the Missing Princes?

The Missing Princes were the sons of King Edward IV of England - Edward V (12) and Richard, Duke of York (9). Both boys disappeared from the royal palace of the Tower of London sometime during 1483-4 where they had been placed by the King’s Council in preparation for Edward’s coronation in June 1483. However, following the revelation of their father’s secret marriage to Eleanor Talbot, the children of King Edward IV were declared bastards by the Three Estates of the Realm and, under medieval Canon Law, were ineligible to succeed to the throne. As the next legitimate heir, their uncle, Richard, Duke of Gloucester, was petitioned to become king. Richard III was crowned at Westminster Abbey on July 6 1483. Shortly afterwards, Richard embarked on a Royal Progress of his new kingdom heading northward to Yorkshire. It was while Richard was absent from the capital that the sons of Edward IV apparently disappeared from the Tower of London. Contemporary sources confirm that the boys were alive in the Tower while Richard was on progress, and later sources that they were alive on or around 8 September when the King was in York (Crowland and Vergil). Crowland also said that by late September, rumours of their death had seemingly been spread by rebels in the south led by Richard’s royal cousin and former ally, Henry Stafford, Duke of Buckingham.

Following the death of King Richard at the battle of Bosworth on 22 August 1485, Henry VII became king. On 18 January 1486, Henry married Elizabeth of York, Edward IV’s eldest daughter. Shortly afterwards Elizabeth was legitimised by the repeal of Titulus Regius, King Richard’s title to the throne. This also legitimised her brothers, Edward and Richard, the missing Princes, making the elder, Edward, rightful King of England. On Sunday 27 May 1487 1 in Dublin, Ireland, a young boy was crowned King Edward of England. The elder ‘Prince in the Tower’ (the former Edward V) would have been 16 years of age at this time. Four years later, a young man from Flanders claimed to be Richard, Duke of York, the youngest son of Edward IV. He too claimed to be the rightful King of England. In this year the younger ‘Prince in the Tower’ would have been 17 years of age.

At face value, this raises an important conundrum: a former King Edward and a former Prince Richard disappeared during the reign of Richard III, now a ‘King Edward’ and a ‘Prince Richard’ reappeared. Were these Claimants the sons of Edward IV? You can read more about the two claimants to Henry VII’s throne here.

1. From a number of sources including the Red Book of Ireland. See: Randolph Jones, Ricardian Bulletin (June 2009), pp.42-4, and Ricardian Bulletin (September 2014, pp.43-5. Also Academia, Medieval Dublin XIV (2015), pp.185-209, specifically Appendix 1: ‘The Revised Coronation Date of Lambert Simnel’, pp.207-209. In the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries a Sunday was the appropriate day for a coronation. It is not known why Henry VII’s Parliament recorded the date of the Dublin coronation as 24 May (a Thursday). This may have been a deliberate attempt to undermine the credibility, and legitimacy, of the ceremony, and thereby its anointed king.

Why do we need a Missing Princes Project?

Put simply, it is to help move our knowledge forward and to attempt to finally come to a definitive conclusion about this enduring royal mystery. The Looking For Richard Project, which discovered Richard III in a car park in Leicester, succeeded because it was prepared to question, rather than simply repeat traditional history. It examined the age-old ‘bones in the river’ story and proved it false. It also introduced science and a multi-disciplinary approach to the study of history: Dr John Ashdown-Hill’s ground-breaking discovery of the king’s mtDNA, and my decision to commission a GPR survey, archaeological dig, and the first-ever Psychological Analysis of Richard III by two of the UK’s leading experts. This new multi-faceted approach is now leading the way for future historical investigations. The strategy is unequivocal; only by questioning received wisdom and dogma can we hope to move our knowledge forward, to learn and to discover.

The discovery of Richard III has exposed many of the myths surrounding this historical figure so that today he is increasingly discussed within the context of his time. This is an important development. Although Richard is a uniquely controversial figure, many commentators through the centuries have merely nailed their colours to the mast of the Tudor portrayal, so that the study of our history remains replete with blind repetition. The preferred route for many is to repeat as fact the rumour, hearsay and gossip proclaiming not only the certain deaths of the Princes within the Tower of London, but also Richard III as the indisputably guilty perpetrator of the crime. All this despite the fact that there is no evidence whatsoever to support either their murder in the Tower, or the king’s culpability. But might it be true? What little evidence we do possess suggests it is unlikely, but The Missing Princes Project aims to question and leave no stone unturned.

What do we hope to achieve?

The ‘murder’ of the ‘Princes in the Tower’ is the enduring mystery that continues to divide opinion and feed the centuries-old debate of good or bad Richard, which ultimately serves only to remove us from the real, the historical. By questioning traditional history and launching this unique investigation we hope to discover the key to one of our most enduring historical mysteries. And by finding the truth, we may finally be able to lay King Richard III - the medieval man and monarch - to rest.

How do we hope to achieve it?

The Missing Princes Project is a Cold Case History investigation employing the same principles and practices as a modern police investigation, and this is what is new. It is not an academic study or exercise although it does naturally involve the examination of all contemporary and near contemporary source material, but it is in its intelligence gathering and modern investigative methodology that offers an exciting opportunity and a new 360 degree approach in terms of this abiding mystery. The modern investigation is employing forensic analysis of the people and events surrounding the disappearance of the sons of Edward IV to open exciting new lines of investigation. At the same time, the project is initiating searches for neglected archival material in the UK and overseas.

Cold Case History Investigation Methodology:

- Introduction of modern Police investigative techniques to facilitate:

- Forensic analysis of existing primary and secondary source material;

- Focus on contemporary source material;

- Construction of detailed Timelines;

- New lines of investigation;

- Application of ‘means, motive, opportunity, proclivity’ analysis;

- ‘Persons of interest’ enquiry;

- Key witness investigation;

- Criminal Search methodology and Profiling systems;

- Searches for neglected archival material - in the UK and overseas;

- Engagement of leading experts including Police and CSI Investigation specialists

- Implementation of ABC Methodology –

Accept Nothing. Believe Nobody. Challenge Everything

So why ‘missing’?

The term ‘missing’ is applied to the project because this is all we know about this mystery based on the available evidence. The Missing Princes Project is, as a result, a Missing Persons Investigation; albeit one that is 500 years-old.

Would you like to be involved?

The project requires a wide range of skillsets, from specialist modern investigative expertise to Palaeography, Latin and key foreign languages such as French, Flemish, Dutch, German, Spanish and Portuguese.

One of the most important aspects of the project is the local initiatives aiming to draw attention to little-known archival material. We believe that new documentary evidence is waiting to be discovered but we require willing volunteers in the UK and overseas. Once located a team of specialists is ready to help. Does your local library or local authority hold any uncatalogued records, is there a local archivist willing to help, or is there a collection of records held by a local family who might allow one of our experts to examine them?

If you would like to help with a search for neglected archival material in your area, then please complete the Confirmation of Interest form.

Thank you, and we look forward to hearing from you.

Registered with the Information Commissioners Office (ICO) for Data Protection

Is it possible to solve the mystery of the Missing Princes?

When I began the Looking For Richard Project it was derided by many within the academic and historical communities as a nonsensical wild goose chase. Many traditional and supposedly authoritative accounts published before August 2012 clearly testified that the remains of Richard III were in the river Soar. But disparagement in all its forms does not, and must not, change or stop what we do. The Missing Princes Project was launched in the summer of 2015 with three lines of investigation. By early 2016 these had developed into twelve. The project currently has thirty-five separate lines of investigation, which, to my knowledge, have not been investigated before.** It looks likely to be a mammoth task, potentially taking many years but nothing worth doing is easy. The Looking For Richard Project took ten years to reach its eventual conclusion with the honourable reburial of King Richard III. Whatever the task ahead of us, what is important is that for the very first time, we are looking.

**December 2016 Update - The Missing Princes Project now has 75 lines of investigation.

** January 2019 Update – The Missing Princes Project now has 111 lines of investigation, with over a third of these (39) in active research.

- January 2019 Announcement: The project is urgently seeking members in the Flanders and Belgium region willing to undertake searches of their local archives. If this might be you, please complete the ‘Confirmation of Interest’ form (above). Thank you. -

By way of an example, a search for the project is now taking place in the local authority archives in Grimsby in Lincolnshire, led by Sharon Lock, former Communications Manager at the Richard III Society. Sharon has uncovered a letter from Henry VII.

Local Archive Search, Grimsby, Lincolnshire, UK:

There is no telling where a relevant piece of evidence with regard to the fate of the ‘Princes’ may be found, which is why it is equally important to look and look again. It is easy to think that there will be nothing to find at your local library or archive because it was perhaps not a town or city which featured with any prominence during 1483. For instance, in her book about the possible fate of one of the missing Princes, Perkin: A Story of Deception, Ann Wroe mentions a letter that was sent by a somewhat insecure Henry VII to all the officers of ports along the eastern coast in 1496 because of his concerns over the possible invasion of rebels sent by Maximilian, King of the Romans. No transcript is given, but the mention of a letter related to this period was enough to send Sharon Lock off to her local archives in Grimsby, in the fifteenth century a small fishing port with some trading connections to the Low Countries. The instructions from the king are clear in that he states:

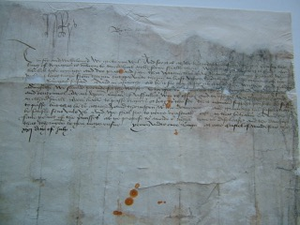

Henry VII’s 1496 letter. Reproduced by kind permission of Lincolnshire Inspire Archives, reference 1/30/7

“we wol and charge you that ye have sure and contyneul wait upon almanner of vessailes wtin yor offices, and in especial wtin the crekes and in othre small rivers hable to passe crayers or botes to the see..”

The letter ends quite strongly by saying,

“…faile ye not of the premises, as ye propose to avoide or right grevious displeasour, and the dangier that thereupon to you may ensue.”

This gives us an insight into just how worried Henry VII was about the invasion of the Yorkist claimant to the throne calling himself 'Richard of England'.

Sharon had no idea that this letter existed in her home town. As a result, she has now discovered that there are other medieval documents in the archives as yet uncatalogued and waiting to be transcribed. This could be a common occurrence around the UK and overseas and we should never assume that everything known has been discovered.

Research is also in progress at Maidstone Library Archives in Kent led by Jean Clare-Tighe, a member of the Richard III Society. Jean has uncovered a curious letter from Richard III.

Local Archive Search, Maidstone, Kent, UK:

Whilst searching for documents at the local archives in Maidstone relating to Thomas Bourchier, Cardinal, and Archbishop of Canterbury for The Missing Princes Project, Jean came across documents held there on behalf of Sandwich Borough Council.

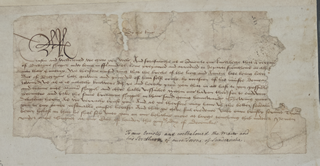

During medieval times Sandwich was a significant English port and the main Kent port situated on the River Stour. With this in mind Jean thought their records would be worth looking into and she uncovered a copy of a letter written by Richard III to the Mayor of Sandwich, bearing the king’s sign manual. The letter is dated 13th December. Although the year is missing, analysis of 1483 and 1484 along with the key months following the rebellion of the autumn of 1483, make the earlier year a much more likely candidate, particularly when it is known that King Richard visited Sandwich for a number of days the following month (13-17 January 1484).

Letter from Richard III, 13 December 1483. (Sa/ZB2/178) Courtesy of Sandwich Town Council & Kent History & Library Centre, Maidstone ©

There was also some doubt cast as to whether this was Richard III’s signature, but this was laid to rest for Jean by Dr Heather Falvey, a specialist in Palaeography at the Richard III Society. Heather explained that the clerk had copied the contents of the original letter, including the signature. It is interesting that King Richard has written quite a detailed letter, but there is clearly something that he does not want to disclose in writing, but has instructed his servant to convey it verbally to the Mayor. His trusty servant, Thomas, has not been given a surname. It could be that by giving his full name conclusions may have then been drawn as to the nature of the additional (and potentially important) information he carried, and to the king’s intent.

King Richard specifies to the Mayor of Sandwich his concern with the Breton shipping at this time and the recent ‘iniuste’ (unjust) actions of the Duke of Brittany that is well-known and commands the Mayor to man all manner of ships there in order to keep watch:

“ … manne oute alman(er) shippes and othre hable vessailes within our haven ther(e) for to endevour (damaged) recountre and take the same bretayne shippes in thair said going homeward(es) Shewing your (damaged) diligenc(es) herin As we verraily trust you. And that ye give ful credence unto oure trusty servaunt Thomas berer¹ herof in that he shal sey unto you on our behalve more at large touching this matier, Yeven under oure Signet at our Cite of london the xiijth day of Decembre.”

¹ That is ‘bearer’, i.e. Thomas brought the letter to Sandwich; his surname is not given.

What was the information his trusty servant Thomas was carrying to the Mayor? Perhaps Jean may uncover more during her searches of the Kent archives.

With thanks to Dr Heather Falvey of the Richard III Society.

'To strive, to seek, to find, and not to yield'

Ulysses by Alfred, Lord Tennyson (1809-1892)

John Dryden (1631-1700) was an English poet, literary critic, translator, and playwright who was made England's first Poet Laureate in 1668.

About Philippa Langley

In 2012, Philippa Langley led the search for Richard III in a council car park in Leicester through her original Looking For Richard Project. Philippa conceived, facilitated and commissioned this unique historical investigation. Following seven and a half years of enquiry, she identified the likely location of the church and grave, instructing exhumation of the human remains uncovered in that exact location. Her project marked the first-ever search for the lost grave of an anointed King of England. She is President of the Scottish Branch of the Richard III Society and in 2015 was awarded Membership of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire (MBE) by HM The Queen at Buckingham Palace.

To find out more about Philippa and her original Looking For Richard Project, please visit: www.philippalangley.co.uk